A Founding Father’s Odyssey: How a Beloved Presidential Bust Made Its Way Home to St. John’s Annapolis

December 20, 2023 | By Kirstin Fawcett

When freshman Robin Chalek Tzannes (A73) met George late in the evening during her first college party in 1969, she found him bruised and battered in the ladies’ room, his torso halfway down the toilet. She knew she had to help him.

How Tzannes would pull off said rescue was another matter. See, George was not just any classmate: the life-size plaster bust, with its badly chipped base and graffiti scrawled across the front (“Some idiot had written ‘A Lincoln,’” Tzannes scoffs), was so heavy she could barely comprehend lifting it, much less fishing it from the john. So Tzannes rejoined the party in Mellon Hall’s Francis Scott Key auditorium, where she recalls, she “found a young man who was strong enough and drunk enough to carry the bust to my dorm.” The newly liberated figure received a place of pride on top of her dresser in Campbell Hall as Tzannes marveled at the odds of it falling into her care.

Some Johnnies love Homer, obsess over Plato, or hanker for Heidegger. Tzannes just happens to be a fan of the nation’s premier Founding Father: amassed through a lifetime of careful curation, her personal collection of Washington-related imagery and memorabilia contains more than 1,000 pieces. “That I, of all people, should have discovered this misplaced, mistreated piece of Washingtonia was no coincidence,” she says. “It was fate.”

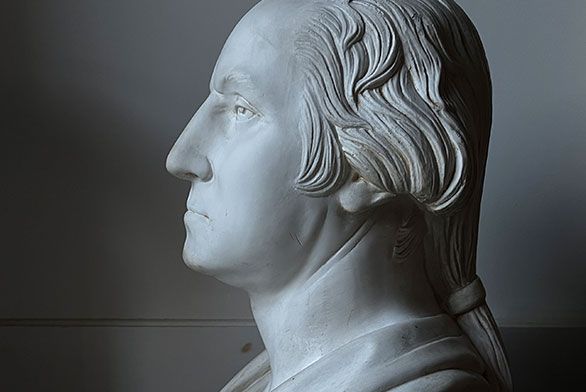

As is often the case with fate, the chain of events leading up to George’s unfortunate baptism is a mystery. Tzannes doesn’t know the campus building he graced, or which Hercules-in-training swiped the statue from his post. What we do know, thanks to her research, is that he is a replica of a marble bust at Mount Vernon, carved from life by renowned French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon. In 1932, the Washington Bicentennial Commission presented a copy to every state in the union. They mostly went to state houses—but since the Maryland State House already had a full-body statue of Washington, they gave their Houdon bust to St. John’s next door. (The gift was fitting, since Washington’s two nephews attended the college and the president himself paid St. John’s an in-person visit in 1791.)

Post-party, a more pressing question loomed: what to do with George? The answer wound up being “nothing” as Tzannes and her roommate awaited side-eyed glances and whispers that never came. “Surely the administration would notice that the bust was missing,” Tzannes recalls thinking. “Or maybe someone seeing it in our room would mention it to the Dean, who would certainly demand its return. But no questions, no notices, no reprimands ever materialized.” And in the blink of an eye, the school year was over—and though she could not have foreseen it, the bust’s journey had just begun. Packing up her dorm, Tzannes “didn’t know what to do with George Washington,” she says. “So, I took him home.”

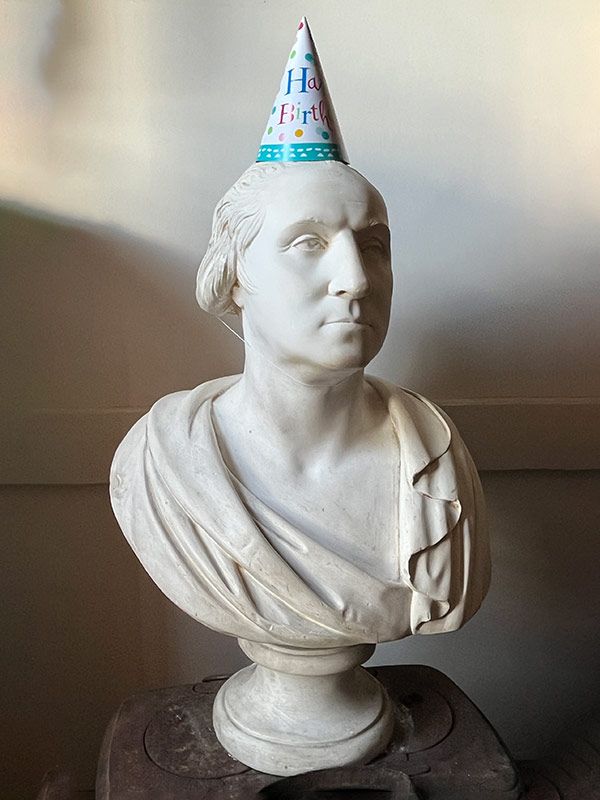

Years passed, and then decades as Tzannes graduated from St. John’s, settled in Manhattan, launched a career in advertising, and started a family—one in which George was considered an honorary member. They even decorated him seasonally: a Santa hat on Christmas; a party hat on his real-life counterpart's birthday, February 22; and masks on Halloween. Occasionally Tzannes and her loved ones (she has two sons who went to St. John’s Santa Fe) joked that she should at some point give George back to the college. Her conscience agreed. “I always wanted to return [him], but the timing never seemed right.” Then, 54 years after that fateful first-year party in Mellon Hall, she learned that Nora Demleitner had been named president of St. John’s Annapolis. Noting the parallels between St. John’s first women president and George Washington, the nation’s first president, Tzannes interpreted Demleitner’s appointment as a sign: George needed to go back to Annapolis.

But how to go about it, considering she did not drive, and lived more than 200 miles away from campus in a fifth-floor walkup apartment? Tzannes ran the dilemma by longtime friend Eva Brann, who advised she contact the St. John’s College New York alumni association chapter. Chapter head Daniel Van Doren (A81), in turn, reached out to senior director of advancement John Kane (AGI10), who agreed to collect George while traveling to New York with Demleitner for a meet-and-greet in spring 2023. Brann also recommended that Tzannes—who, fittingly enough, lives part-time in Greece on the island of Kythira, where Odysseus’ ship is said to have been blown back to sea—detail the entire odyssey to Demleitner. Worried she would be judged or condemned, she nonetheless recounted George’s peripatetic past during their very first face-to-face meeting. “The first thing she said to me was, “What a great story,’” Tzannes says. “Her reaction was exactly what I was hoping for.”

Today, the plaster bust of George Washington sits in a corner alcove in the Harrison Alumni Center: waiting for a permanent home on campus (potentially in Mellon Hall) and an enterprising historian to dig up more on his past. For now, at least, his days on the move are done.

Do you have memories of St. John’s George Washington bust or know anything about its past? Email with stories, tips, and history tidbits.