Scholars Discover Original Locke Manuscript in Greenfield Library

August 15, 2019 | By Kimberly Uslin

It was through the winning combination of “serendipity and lots of Google,” scholar J.C. Walmsley says, that he happened upon an unknown John Locke manuscript in the archives of the Greenfield Library on the Annapolis campus of St. John’s College.

Walmsley’s search for little-known writings from the 17th-century philosopher was inspired by fellow Locke scholar Felix Waldmann, who had recently discovered a number of books that had been part of Locke’s personal library. Walmsley was curious to see whether there was more to be unearthed in the form of manuscripts.

“Sure enough, he found this reference to the manuscript in a Maggs Bros. book catalogue from the 1920s and thought ‘Well, I’ve never heard of this manuscript before,’” tells Waldmann. “St. John’s College library does not own any other manuscripts by John Locke or any other books that derived from his library, so it was really through Craig’s persistence and ingenuity that he found the document.”

Walmsley got in touch with the St. John’s staff at the Greenfield Library, who found the manuscript, scanned it, and sent it along to him. (“I want to just say thank you to Catherine Dixon and Cara Sabolcik for their help in tracking this thing down,” he adds. “They were incredibly helpful and really quite generous with their time.”)

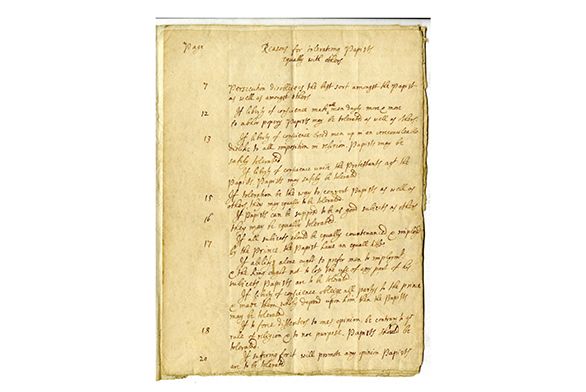

He knew immediately that he’d struck historical gold—a completely unknown manuscript in John Locke’s own hand entitled Reasons for tolerateing Papists equally with others.

It was a unique find; in the world of Locke scholarship, there is a fairly definitive online bibliography of more than 8,000 of the philosopher’s works, from books and treatises to notes and letters. The Reasons for tolerateing Papists manuscript was not among them.

“It was amazing because it was obviously a Locke manuscript. There was no mistake about that. St. John’s was in possession of a very rare item even by the standards of major U.S. libraries,” he recalls. “And the content was really, really interesting.”

According to Walmsley and Waldmann, this was the first major discovery of new work by Locke in a generation. While there are occasionally unseen letters or signed documents found, something this “substantial in content” is incredibly rare—particularly because it represented a previously unknown perspective held by Locke.

The manuscript essentially consists of two lists: the first, a set of reasons for tolerating Catholics, which at the time simply meant not actively persecuting the group, and the second a list of reasons not to (which is his much wider-known opinion).

According to Walmsley, the manuscript is directly connected to Locke’s Essay concerning Toleration, and, he says “was most likely its immediate antecedent and inspiration.”

“The early drafts of the Essay read like successively more elaborate treatments of questions raised in the Reasons, and parts of the Reasons re-appear in later drafts of the Essay. The Essay was Locke’s first mature formulation of the views that would be immensely important,” Walmsley adds. “When repeated in the Letters on Toleration, these arguments would indelibly inform Western liberal thinking in general and the U.S. Constitution in particular.”

“Today we would call it brainstorming,” says Cole Simmons (A09), a St. John’s alumnus and lecturer at Baylor University who wrote his PhD dissertation on Locke and toleration. “Everyone kind of has down that Locke doesn’t and isn’t willing to tolerate Catholics, so the surprising thing is that he entertained tolerating Catholics for some time. But the reasons for tolerating and not tolerating are very Lockean, in either respect: When he gives reasons for tolerating Catholics, all of the reasons are to the prince’s interest—basically, if [toleration] can benefit the Commonwealth or the prince, you should tolerate Catholics. And the second list is ‘if not tolerating Catholics will benefit the prince or the Commonwealth, you shouldn’t tolerate Catholics.’”

“Toleration is important because you can’t force people to change their minds and believe something they don’t,” he adds. “Toleration allowed for people to continue to believe what they believed without leading to those horrible consequences of civil strife.”

(Incidentally, Maryland was among the first of the colonies to pass a law requiring religious tolerance in the form of the 1649 Maryland Toleration Act.)

Walmsley and Waldmann worked together with other scholars to decode the historical and philosophical context of the manuscript and its place within Locke’s oeuvre. One of their most critical discoveries was the clear indication that the manuscript was responding to a work by Sir Charles Wolseley, which scholars had previously suspected Locke had read, but which could not otherwise be demonstrated.

“There’s a type of ambivalence when you do discover things: It’s always rather enjoyable, but then you’re invariably confronted with the difficulty of making it intelligible to the public,” Waldmann says. “It’s not just a case of transcribing it and saying ‘Look, here’s what I found,’ and throwing it out to the public to read.”

“Trying to make sense of what this manuscript means was a challenge, and really would have been a challenge for any scholar of any standing,” he adds, “because on the surface of the manuscript, its very title—Reasons for tolerateing papists equally with others—is, I think it’s fair to say, extremely far from what anyone would have expected to find in Locke’s handwriting.”

While the St. John’s seminar reading list does not include any of Locke’s works on religious toleration, students do read his Second Treatise of Government, and the Reasons for tolerateing Papists equally with others is useful in understanding the development of Locke’s thought—and perhaps more importantly, says Simmons, serves as a potential “enticement to scholarship” for St. John’s students.

“It’s very exciting,” he says. “I can’t imagine being Dr. Walmsley and having this in front of you, having this debate whether Locke read Wolseley, and then you prove it—and not only do you prove it, you get to read something in his own hand that has never been published.”

The excitement is certainly not lost on Walmsley.

“In terms of the significance of this and the feeling of finding this thing, I don’t think it’s over-exaggerating to say this is probably the most important thing I will do in my scholarly career,” says Walmsley. “Locke is a hugely influential figure, and to find something completely new—it’s not like you’re writing an interesting argument. It has never been seen before or discussed. And it being a really quite interesting discovery in and of itself, a crucial part of his intellectual development? That’s pretty powerful stuff if you’re an intellectual historian.”

Find the manuscript on the Greenfield Library’s Digital Archives here. Walmsley and Waldmann’s article on the discovery of the manuscript and its implications, “John Locke and the Toleration of Catholics: A New Manuscript” can be found in The Historical Journal, a Cambridge University Press publication.