Why Reverend Dr. Hector Humphreys, the College's Fifth President, Was a Quintessential Johnnie

By Whitney Bixby (A25) | November 14, 2025

“I have lived to no purpose if I have not planted the seeds of perfect Virtue in the hearts and minds of my Pupils,” said the Reverend Dr. Hector Humphreys, the fifth president of St. John’s College, in his Baccalaureate sermon at Commencement 1852.

Despite having lived in Humphreys Hall, named for the early college leader, I had not known who Humphreys was until last summer. At that time, I had begun rehousing his personal papers as part of my archival internship with the Greenfield Library, a position supported through the St. John’s College Internship Funding Program.

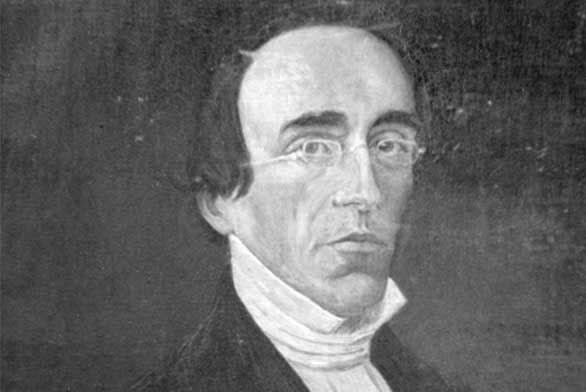

Humphreys served in his role as president for 26 years, entering the office in 1831 amid a state of financial turmoil and remaining there until his 1857 death. The State of Maryland had withdrawn St. John’s funding, and the college struggled to acquire the means to provide students with a proper education. Humphreys strove to improve circumstances throughout his presidency by securing supplies for science programs, building a laboratory, increasing the number of books in the library, and, toward the end of his tenure, constructing a new hall that St. John’s would posthumously name in his honor.

Humphreys was a humble man, and although his speeches and sermons were admired by many, he did not wish to publish them. Thus, his surviving works are scarce, and his Baccalaureate sermon may have been lost to obscurity had his personal handwritten copy not found its way to the St. John’s College Archives and into my hands more than 150 years later.

I found Humphreys’ 1852 homily alongside five additional handwritten sermons, an agricultural manual he had composed on the chemistry of soil and manure, and several letters addressed to him between 1821-1856. These papers were all in good condition, save a couple that were torn, brittle, and/or covered in masking tape (a nightmare for archivists, as it damages paper over time).

A browned piece of paper among these materials stated that a collection of Humphreys’ personal writings had been given to St. John’s College sometime during Dr. Richard D. Weigle’s presidency by a Ms. Burton Bright, although it is a mystery as to where they had been before that. As for Bright, who was born Burton Munroe Starr in 1888, she had married Rear Admiral Clarkson J. Bright, a Naval Academy graduate and future faculty member, in 1912, and died in 1978 at age 89. Her stepfather was William Learned Macy, a St. John’s tutor and the son of Humphreys’ daughter, Eliza Mott Humphreys.

Now an intern at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, I learned how to process archival collections during my time at the Greenfield Library, preserving items while making them more accessible to researchers. This included ensuring said documents were properly housed in labeled folders, organizing and regrouping them, and creating a finding aid—an online resource for researchers to determine the contents of a collection. I worked with Humphreys’s papers over the course of a few weeks, and, using the website From The Page, I transcribed them so his script is easier to read.

I perused most of Humphreys’ papers to determine the scope and contents for a finding aid, and, as I read, I began to piece together who he was as a person. I began with his letters, which were written to him by students and colleagues from Yale (his alma mater) and Trinity College (where he taught before coming to St. John’s), as well as by church colleagues and his niece. One writer detailed to Humphreys his life as a student at seminary; another, from his niece, detailed in gorgeous cursive how she and his mother wished he would visit. The letter I was most interested in, however, was from a professor at Yale who wrote about scientific apparatus being developed in London and Paris related to electromagnetism as well as diffraction and polarization of light—topics studied at St. John’s in undergrads’ junior year laboratory. The letter was a testament to Humphreys’ passion for the sciences, and his quest to improve research amenities at St. John’s.

Humphreys not only acted as the college’s president but was directly involved in its curriculum, as he taught science, natural philosophy, and astronomy as well as Greek and Latin. In fact, in a list of the faculty from 1852, Humphreys is listed both as the president and as a “Professor of Moral Science,” demonstrating his interest in teaching his students virtue beyond the physical sciences. He is also described in a biography as having taken an interest in Euclid during his studies at Yale. In these ways, Humphreys embodied the St. John’s Program long before it was implemented in 1937, 80 years after his death.

Humphreys was heavily involved in the St. John’s College community, and he also engaged in Christian ministry around Annapolis. The five sermons in our library archives were delivered at local churches such as St. Anne’s Episcopal Church, All Hallows Church, and St. Margaret’s Church, as well as at the Naval Academy. One of these speeches I transcribed, titled “Wonders of the Deep,” spoke about a Christian’s relationship to the ocean; it was poetic and commanding while demonstrating Humphreys’ scientific bent.

The clearest example of this can be found in a passage that, curiously, was partially struck through; Humphreys praises God and his regulation of particles, saying: “It is He who blows the elements of the atmosphere in portions so exact, that to increase or diminish either, would diffuse death instead of life. Behold, then, this Grand Regulator of Heat and Cold ... ” Humphreys excised a portion of this paragraph, but we can glean from reading it in its entirety how his scientific views blend with religion, and how his understanding of particles is used to praise his God. Even in his sermons, we get a sense of Humphreys’ interdisciplinary approach to education.

The item that fascinated me most in Humphreys’ papers was his farmers’ manual. Humphreys produced nearly 100 pages and drew clear and precise diagrams to illustrate his experiments. I was drawn to his skillful illustrations and thoroughness. I was also intrigued by questions that I could not answer, such as, “What inspired Humphreys to dive so deeply into this topic?” We can see that Humphreys was a man who was strongly devoted to scientific inquiry, and his passion for teaching allowed him to share science with others—even local farmers. It seems, in fact, as if there was no academic discipline Humphreys didn't tackle, and I feel that an unrelenting search for knowledge across any area is a characteristic of St. John's students across decades, if not centuries, in this case.

Following a summer spent making Humphreys’ papers more accessible to the public, I became acquainted with the president who revived St. John’s College when it was in critical condition. While fewer than 30 items, they present a compelling image of an influential leader. The portrait of the stern-looking man hanging in McDowell Hall now resembles to me a man motivated by interdisciplinary learning, Christianity, and care for his students. Instead of a stranger, I now see a Johnnie.