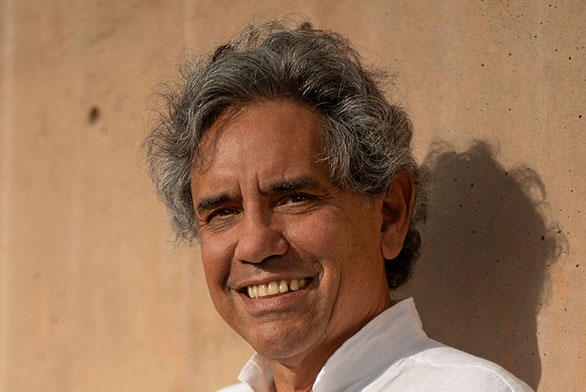

Architect Devendra Contractor (SF79) Describes His Vision for Santa Fe’s New Vladem Contemporary and O'Keeffe Museums

Contractor’s firm, DNCA, designed new buildings for both cultural institutions drawing not just from the city’s historic architecture but from poetry, philosophy, and metaphysics.

June 27, 2023 | By Jennifer Levin

Ask Devendra Contractor (SF79) about his architectural style, and he will paraphrase a passage from Wind, Sand, and Stars, French author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s memoir of wartime flying.

“He’s stranded in the desert and goes to sleep on a sand dune. He wakes up and is overwhelmed by the expanse of the sky and the cosmos. He has a sense of vertigo as if he could just fall off the earth,” Contractor says. “And he has an awareness of what grounds him—not just gravity, but also the nature of memory. The memories that he talks about in that experience have to do with place, and his childhood, and the home that he grew up in.”

Contractor often talks about literature with his colleagues at DNCA Architects, his small, award-winning firm in Santa Fe. When designing a new project, they engage broadly in ideas, bringing poetry, philosophy, and metaphysics into consideration of space, line, and light. Though he’s the firm’s principal with his name on the door, Contractor says that all DNCA projects result from this shared vision process.

“There’s a misconception that architecture is about the individual. It’s about a culture within a studio,” he says.

The current conversation around the worktable is about the new Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. This larger space will replace the old Safeway building on Grant Avenue, about a block from the private museum’s present location. On the studio wall is a grid of O’Keeffe-related images—a few of her paintings, as well as angles of cliff against sky. The new building will be connected by a courtyard to an existing research center, creating a museum campus just west of the Santa Fe Plaza. The neighborhood is known for its historic Territorial Revival architecture—and for undergoing little new construction.

“Our intent will meet all the requirements of the historic code but still maintain a high level of authenticity and allow the building to be iconic, responding to Santa Fe Style [also known as Pueblo style or Spanish Pueblo style] but having a presence within that,” Contractor says. Because the basic structure of the O’Keeffe Museum campus sounds very much like an archetypal O’Keeffe painting, they’re resisting the impulse to be too literal. “I think the power of O’Keeffe’s work is that, like with all good artists, it teaches you how to see and how to engage with a place.”

Contractor grew up outside of Mumbai, India. His parents were architects, and his grandparents were artists who lived in Santa Fe and Taos. His sister also graduated from St. John’s in the 1960s with one of the Santa Fe campus’ first classes. Contractor chose the college because he liked the way his sister could talk about any subject, and he loved the Iliad and was excited that it was the Program’s first book. During college, he worked with the progressive conservationist thinkers at Santa Fe County’s Syngeria Ranch, helping to build the locally renowned all-adobe Llano Compound on East Palace Avenue under the direction of Phil Hawes, a student of Frank Lloyd Wright.

“Everything was locally sourced; it was about vernacular materials, vernacular design,” Contractor says. “I started out mixing mud, then laying adobes, then being foreman on several of the houses. I took a year off from St. John’s to do that. After I graduated, I had my own construction company here, laying adobes and doing stonework.”

Although his parents were architects–his father even hired him for a few years in India–Contractor never seriously considered pursuing the profession. “I didn’t think I was smart enough,” he recalls. “I learned to think about everything at St. John’s but didn’t learn the confidence to do everything.”

He wishes he’d had the opportunity to pursue internships and receive the kind of career guidance that’s today coordinated through the college’s Office of Personal and Professional Development. But in the end, a beloved St. John’s Santa Fe tutor, Ralph Swentzell (1938–2005), convinced him to go to architecture school. The two had run into each other at the city’s DeVargas Mall shopping center; Swentzell, according to his former pupil, used the occasion to say, “‘Contractor, if you don’t go, I’ll never talk to you again.’”

“Ralph was a tremendous mentor and force in my life,” Contractor adds. “I had music class with him and junior math class, and he was my senior advisor. He was one of those people who had an incredibly inquisitive mind and I think was so inspiring to many, many Johnnies.”

All Contractor needed was the right push. When he sat down in his first class, he knew he was home: “I realized I’d actually grown up in that culture. Some of the more famous Western architects were friends of my parents, and they’d come visit our home. I listened to them. I’d absorbed the vocabulary, the way of looking at the world. And I had the math program at St. John’s—I loved the math program. In architecture school, I knew more math than just about anyone in my class.”

Contractor formed DNCA Architects in 2002 after earning his master’s degree in architecture and planning from the University of New Mexico and then serving as a senior associate for Albuquerque-based architect Antoine Predock. Contractor moved his practice to Santa Fe in 2020 when he received the opportunity to design Shoofly Pie, a live/work-space in the Baca Street neighborhood that includes Pie Projects, his wife Alina Boyko’s art gallery.

Shoofly Pie’s exterior is a mixture of corrugated metal and boxy concrete—a contemporary abstraction of traditional Santa Fe style that’s popping up in more and more areas of town. Inside, there are private offices as well as open-plan work areas. With Shoofly Pie, Contractor indulged his love for airy spaces and the tension of opposites: It feels at once like a modernist urban office building, a funky Soho loft, a classic Santa Fe adobe, and something harder to pinpoint, something otherworldly. And all these parts form a seamless whole. The structure stands out as a dignified work of design and fits in perfectly with the area’s eclectic vibe.

Though a variety of architects are contributing to this new Santa Fe aesthetic, DNCA is behind the designs of several gallery buildings in the city’s Railyard District, as well as the Vladem Contemporary, which opens this fall on the corner of Guadalupe Street and Montezuma Avenue. Contractor emphasizes that this more industrial version of Santa Fe Style was part of the revitalized Railyard District’s master plan and that he’s not trying to singlehandedly create a new look for the city. “Each project was a response to authenticity, to a sense of place, a commitment to community,” he says. “The Vladem is very much about that story. It invites the public to engage with it.”

The Vladem Contemporary is the New Mexico Museum of Art’s new venue for contemporary art. (The flagship institution, located on downtown Santa Fe’s Palace Avenue, was built in 1917 and long ago outgrew its exhibition and storage space.) Its ground floor began life as the Charles Ilfeld Company mercantile warehouse in 1936, built on the site of an old coalfield. In recent decades, it housed state offices and archives. And now, Contractor is overseeing the nearly 90-year-old building’s conversion into an art museum.

“The design evolved around a series of conversations that had to do with the nature of preservation,” Calendar says. “We were given an old warehouse building. How do we preserve it? From that conversation, we generated a series of gestural responses that had to do with protection.”

You can hear echoes of Wind, Sand, and Stars as he shows off a small model of the gesture—an opaque cube topped by an arch of translucent blue-green glass.

“The intent was to have a building that spans over it but that aligns with Guadalupe Street itself,” he explains. “The idea is that where it touches the ground, we wanted that to be concrete because that has a solidity rising out of the earth. And then there’s a piece almost floating above it.”