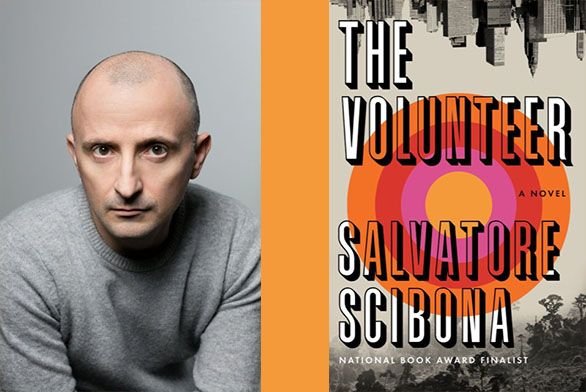

Author Salvatore Scibona (SF97) on Novel Writing, Newton, and New Mexico

March 20, 2019 | By Eve Tolpa

On March 27, Salvatore Scibona is reading from his new novel at a Dean’s Lecture Series talk (funded by the Carol J. Worrell Series on Literature) entitled “On The Volunteer,” at 7:30 p.m. in the Great Hall, with a book signing/question period immediately following in the Junior Common Room.

New Mexico plays a big role in your new novel, The Volunteer. What is your relationship with the state?

My relationship with New Mexico is my time at St. John’s—plus the 20 years since graduation of ongoing inner dialogue that St. John’s made possible and that happens in a second New Mexico of the mind. I read the newspaper on the subway in Manhattan; an ad makes me think of the Nicomachean Ethics; this thinking seems to take place among monsoon rainbows and piñon smoke, while the train rolls on in the dark.

A teacher in graduate school [the Iowa Writers’ Workshop], the novelist Marilynne Robinson, once told me the point of an education was to make a mind you wanted to live in. St. John’s has done that, and the sensory data of daily life there is still strangely wrapped up for me in any experience of concentrated thinking.

What about New Mexico made you feel it would be a good location for parts of the story?

I wouldn’t quite say New Mexico felt like a good location for the story. For me, no story precedes its location. If physical detail is the substance of story, and I think it is, location brings with it details both complex and helpfully limited: When you set a story in Pecos, New Mexico, a river awaits you, certain kinds of trout in the river, picnic stops along the gravel road. The specificity of the place gives the writer something to present to the reader’s hungry senses, and the reader shapes the details into a physical structure that can hold the more abstract aspects of the story, its themes, its psychology, its dream logic.

For example, I have a private mythology about the promise I felt when I first got to St. John’s as a student. Without the context of physical details, I can’t communicate or even recall that promise with any clarity. In 1993, I drove with a friend of my brother’s in a 13-year-old Monte Carlo from Cleveland to New Mexico, sleeping on a floor in Killeen, Texas, and otherwise in the car on the highway shoulder.

In Albuquerque, I dropped off my brother’s friend and headed north to Santa Fe on my own. I was 18 and had never lived away from home before, and I pulled into St. John’s and parked and got out and walked down the sidewalk above the arroyo (a word I didn’t know at the time), which was filled with a thousand plant and animal species, none of which I could name, and I felt more or less that I had been given a second crack at life.

One of the novel’s themes that most resonated with me was regarding the self: What does it mean to be someone or no one? What is the self? Where does it reside?

Maybe nowhere, you know? I feel sympathetic with the Zen tradition, in which, at least as I understand from practitioners, the self is not a potential to be actualized but an illusion to be dispelled. Hume is helpful here: his idea that the self is not a thing but a bundle of experiences.

These questions are at the heart of The Volunteer: Is the self an illusion? Can you leave it behind? And, because the medium of fiction plays out in drama made of physical detail, how would that look, to leave your self behind and yet to keep on living? What would it cost you? As the book went on, all this gave birth to a further question: If you had no self, what would that cost the people around you?

Your two novels, The End and The Volunteer, are currently being read and discussed in a St. John’s community seminar. What is that like for you?

I haven’t participated in one, so I don’t know. The reader is an abstraction to me. My more immediate experience is of the language the reader and I share, the sound and visual shape of a word, the history it bears (Emerson: “Language is fossil poetry”), the hope for clarity and plainness and control, which is always in competition with grace—that is, with the force of things that come at you from out of your control, the way sleep and fear invade the Greek camp in the Iliad, from the outside in.

The reader is a coequal participant with the writer in this competition—a better word would be “opposition”—between control and grace, performing and undergoing it herself as she reads. But in a fundamental way, she doesn’t know who I am, and I don’t know who she is.

Are there any particular Program texts that left a strong impression on you as a student or that stuck with you longer than expected?

It’s a mark of the coherence of the curriculum that the books aren’t a pile of separate texts in my mind but a web of interconnected thought. Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, which I read in a preceptorial and which follows six people from earliest consciousness to old age, is inextricable in my mind from the arguments over planetary motion in Ptolemy, Copernicus, and Newton. The people in the novel move with their own straight, individual momentum, while also tending toward charismatic other people. This compound motion makes a curve that describes a life—or a planet revolving around a star. The Principia still seems to me a thorough description of the way we maintain our individuality while under the influence—via love, domination, repugnance, friendship—of another person.

Has your view of your education changed over the years?

I’m as liable as the next person to let nostalgia cover my memory in rose petals, but it is an explicit claim of the Program that the books one reads there are lasting and, to use the freighted word, “great.” I think it was Mortimer Adler who said their greatness came from the way they paid new insights no matter how many times you read them. In this sense, they are not old, they are new. A book published last year that speaks in a limited way only to matters of the moment becomes old right away, like a newspaper.

I have not gone back and reread Leibniz. Epictetus, however, I just started again last week. The education—the books—largely formed the architecture of the mind I live in. Passages I haven’t thought about it in 20 years come to me multiple times a day, every day. Meantime the web, the whole structure of inquiry that is the Program has had an influence that, as George Eliot says of the effect of Dorothea on those around her, has been “incalculably diffusive.”

The mind is practically infinite, and yet it goes on expanding, over time, like the universe since the big bang. The means of the mind’s expansion are continuing thought and experience. I don’t believe in a firm separation between the real-time experience of these books and how I view them in hindsight. A different kind of time governs the unfolding of our understanding of them.

I never failed to be shocked at the way I would read a seminar book firmly convinced that every word was flying right over my head—and then the next day in seminar the conversation would reveal that while consciously I had experienced only frustration, my unconscious had still been paying its weird attention, storing observations, phrases, moments, the placement of a name on the page. I had read more than I was aware, and this goes on being true.