Existentialism at the Border: Graduate Institute Students Merge Documentary Photography and Philosophy

August 11, 2023 | By Jennifer Levin

Migrating from Latin America to the United States requires tremendous physical, mental, and emotional strength. If you don’t have a visa, you might make the trip through several countries by caravanning with others, paying smugglers to transport you, and even crawling through the desert in the dark, flattening your body to the ground every few minutes to evade detection. Finally arriving at the Paso del Norte bridge that separates Ciudad Juárez from El Paso, Texas, is evidence of an internal fortitude that not everyone possesses, as well as the basic ability to make the journey on foot. But it’s at this stage, says photographer Armando Rodriguez (AGI23), that the real test of will begins.

“You go through the immigration process. You have to deal with border patrol…and they are not well known for their humane approach. During the COVID-era Title 42 policy, migrants established camps in the desert, enduring high heat for weeks just waiting to gain entrance into the U.S.,” says Rodriguez, who works as a regional admissions counselor for St. John’s College Santa Fe from El Paso and recently completed the St. John’s Graduate Institute in Annapolis as a low-residency student. Though he didn’t come over the Paso del Norte bridge, he migrated from Mexico when he was in his mid-twenties.

The immigration process starts the moment one arrives at the border. This is when time stops. To illustrate this precarious existence—when you can’t go back but you don’t know what the future holds—Rodriguez is creating a multimedia documentary project, Limbo: Historias de un Migrante. The final project will include photographs, videos, interviews, short articles, and philosophy. He’s working on the project remotely with Gabe Coronado (AGI24), a St. John’s graduate student who met Rodriguez last year in a Kierkegaard preceptorial.

“I reached out to him because he had a Latino surname, and we formed a friendship from there,” says Coronado, a Maryland resident who immigrated from Guatemala when he was a child—and became a U.S. citizen in June. Discussing Rodriguez’s photos from the bridge, and their connections to Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, quickly led to Coronado translating video interviews and writing text.

“The project was growing,” Rodriguez says. Although the partnership was unofficial at first, Coronado is now listed as a collaborator on the project website, and he secured internship funding through the St. John’s Career Development Office to purchase technology that supports his work. Rodriguez likens their partnership to that of Achilles and Patroclus in the Iliad—the perfect Greek unit. “It is all about finding those people who will complement your journey in life.”

Coronado has cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchair. Although his family was part of upper-middle class society in Guatemala, support for disabilities in his home country is nearly non-existent, he says, and his parents didn’t want him confined to a life in bed, without educational or social opportunities. They were able to come to the United States—“where the Americans with Disabilities Act exists,” he notes—but they had to give up their wealth and start over. “My parents worked 12-hour days to keep food on the table for me and my brothers,” he says. (Read more of Coronado’s story.)

Limbo isn’t a political project, but an exploration of the human spirit rooted in the study of Kierkegaard’s existentialism and Nietzsche’s imperative to overcome oneself. “It’s about the will to power,” Rodriguez says. Coronado takes a more Kierkegaardian perspective: “He talks about how inside of you, there’s a true self. The ‘sickness unto death’ is the despair that you face as a human being, that suffering of not being who you are. It is that suffering that sometimes you have for not living to your main potential. He said it’s by learning how to be anxious in the right way, and taking that leap of faith, that you transform into the being you’re supposed to be.”

The will to do whatever it takes to make it through several Latin American countries is the same will that leads immigrants to start over in a new home while saving enough to open businesses and contribute to the richness of life in the United States—where newcomers from countries like Italy and Ireland made New York City great, for instance, Rodriguez says. “They have a fresh belief in the American Dream, with no notion of the difficult challenges that everyday people in the U.S. endure. They are simply led by faith.” But one of the nuances he still wants to convey in Limbo is also the way the will shifts when you get to the final leg of the trip: the border.

“When you’re lining up at the Juárez side, everyone will cut you off and everything is very aggressive,” he says. “It’s not pleasant. But as soon as you cross to the American side, everyone becomes more civil, everyone helps each other. The same people change based on that imaginary line that separates both countries.”

Coronado offers an example from an interview in which a man says that until he got to the U.S., he passed through countries with their own asylum processes without declaring himself. But once in Juárez, he wanted to follow proper procedures for getting into the United States. “For 90 percent of the journey he circumvented the law,” Coronado says, “and then the last 10 percent, he was so committed to following the law. That really shows that the border is the first encounter of a clash of cultures and the history of Latin American rule of law.”

They explain that despite laws being unevenly enforced in the U.S., the basic rule of law is respected, whereas in Latin America, the law is not always stable, nor are there always strong individual protections or political freedoms. “I don’t think it’s wise for an immigrant to surrender themselves to the Mexican or Guatemalan authorities. That’s like renouncing one’s life,” Rodriguez says.

When Rodriguez came to the United States, he spent many years focused on getting from one day to the next. Of his life now, he says, “Customs are kings; they are part of our self-understanding. I moved to El Paso to be closer to those customs. When that is taken away from you, it’s like taking away part of who you are as an individual. Like, how you understand yourself as an American, living in China, it’s different. That sense of longing made me become a photographer. I was trying to express that feeling of deep anxiety, of the waiting, of not knowing what is going to happen to you in the future, while at the same time, the memory of home becomes even greater, taking you as its prisoner, dwarfing every notion of the future. Limbo came about when I finally read Kierkegaard, and I knew I needed to become myself, to come back to my true self.”

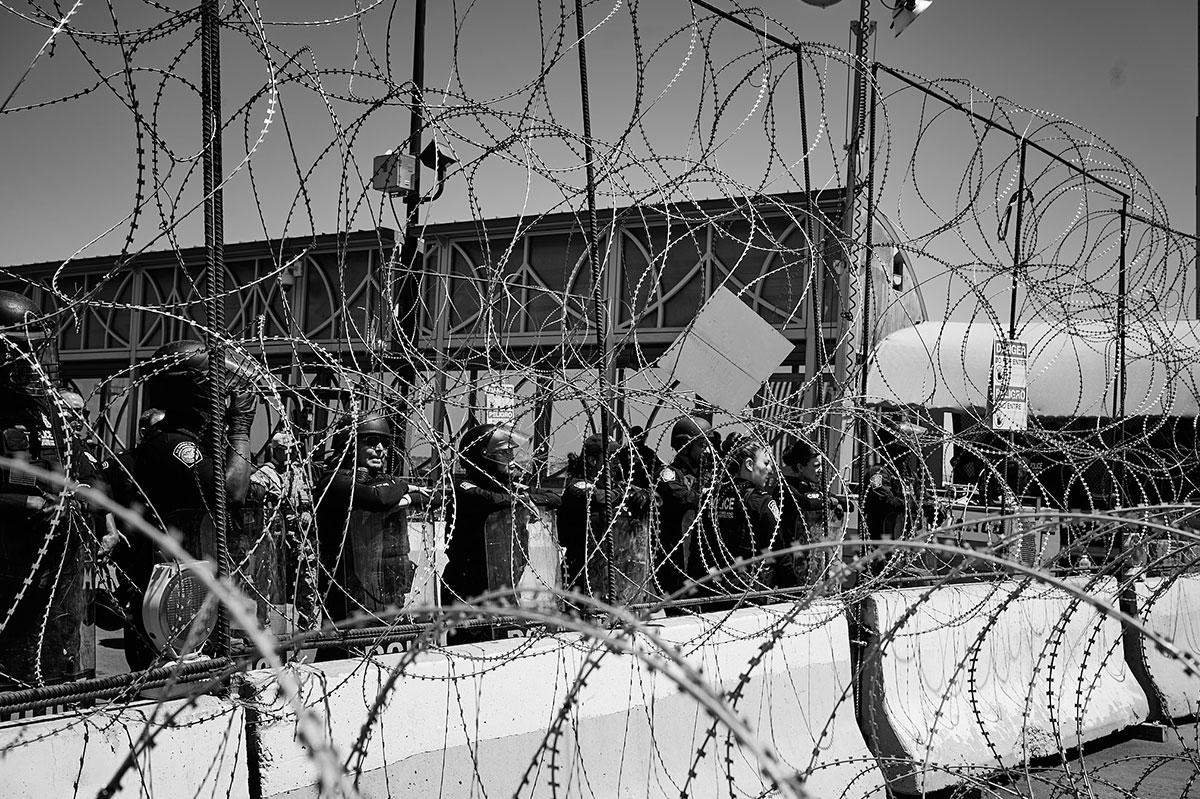

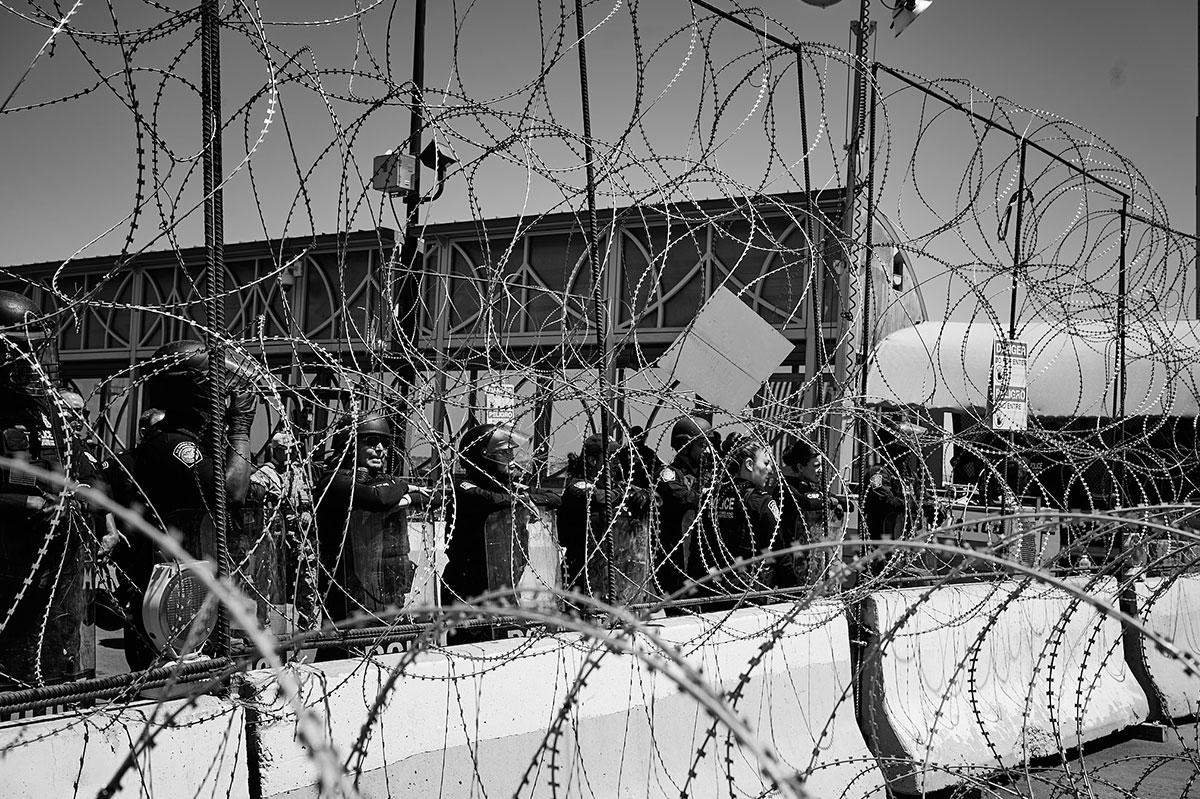

When a group stormed the Paso del Norte bridge in March 2023, he wanted to run downtown with his camera, but anxiety defeated him. He stayed home, full of regret. A month later, it happened again, and Limbo was born. “It was a second chance to live,” Rodriguez recalls. “That day, I finally got the existentialist call to action. I took a leap of faith, picked up my camera, and headed to the scene. I crossed to Juárez through another bridge, said I was an independent journalist, and mixed myself with the press. That day changed who I am. It was a revelation to me, of the individual I needed to become. That is when the project started. I was finally in sync with my inner self and understood my life’s purpose. That day, Kierkegaard struck me like a lightning bolt: ‘To dare is to lose one’s footing momentarily. Not to dare is to lose oneself.’”

View some scenes from Limbo below. (All photos by Armando Rodriguez, apart from image of Gabe Coronado)

-

Alejandra, who’s from Peru, embraces her children under a bridge right on the U.S.-Mexico border. Launch Photo Gallery -

Alejandra prepares to enter the U.S. following six months of travel. Launch Photo Gallery -

Jhorman, who hails from Venezuela, contemplates his life the morning before his processing date to enter the U.S. Launch Photo Gallery -

Border Patrol agents line up, ready to face a group on the bridge between Juárez and El Paso. Launch Photo Gallery -

Photographer Rodriguez (left) finishes a photo shoot at a refugee camp in the streets of downtown El Paso. Launch Photo Gallery -

A girl in the Texas desert is captivated by the media spectacle occurring across the river. Launch Photo Gallery -

Rodriguez poses for a selfie with Alejandra and her daughter after the two gain entry to the U.S. Launch Photo Gallery -

A group awaits processing in the desert after the end of the COVID-era Title 42 policy as the National Guard keeps watch. Launch Photo Gallery -

Jariely, who’s from Venezuela, holds her baby at the U.S.-Mexico border. The following day, she surrendered herself to the border patrol. Launch Photo Gallery -

A family stands opposite the National Guard as they realize the border has been closed by a barbed-wire fence. Launch Photo Gallery -

Gabe Coronado (AGI24) proudly waves an American flag after receiving his citizenship following 22 years of life in the U.S. Launch Photo Gallery