Flashback: St. John’s Postpones Fall 1918 Semester

November 16, 2020 | By Les Poling

In March of 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic spread rapidly across the world, countries and communities entered strict lockdowns and St. John’s College closed its campuses. First, students took leave of dormitories and classrooms in Santa Fe and Annapolis for the remainder of the spring semester. Then, St. John’s moved to remote learning for Fall 2020, marking an extraordinary first for the college.

But for the Annapolis campus, that first was actually more of a second. While St. John’s in 1918 bore little resemblance to the present-day college—Stringfellow Barr and Scott Buchanan had not yet introduced their revolutionary Great Books Program—one striking similarity was the onset of the 1918 flu and its consequences. Like in 2020, 1918’s global pandemic forced St. John’s to postpone the fall term (and quarantine 400 students on campus).

The college had originally been scheduled to open on September 18, 1918. But due to a small outbreak of influenza cases, the start date was pushed back to September 25, and again to October 1. Then, according to an article in The Capital dated September 30, 1918, “on account of the appearance among the students of the Spanish ‘flu’ St. John’s will not open for another week, October 8.”

The article continued: “Five cases of the disease were discovered among the 400 students… Many of the students were out in the town when the quarantine was declared. They did not know whether to go back to the school or to return to their homes until the quarantine was lifted. Their induction into the Students’ Army Training Corps has been postponed until October 8.” A sense of limbo descended on Annapolis Johnnies—an eerie preview of last spring.

The 1918 flu is one of the only cultural reference points we have, in 2020, for the catastrophic effects of COVID-19. According to the CDC, the H1N1 “Spanish flu” virus emerged in early 1918—first discovered in the United States among military personnel—and, over the next two years, infected approximately 500 million people, around one-third of the world’s population. The worldwide death toll reached at least 50 million, with an estimated 675,000 deaths in the U.S. And like COVID-19 (for the time being), there was no vaccine. Measures taken to curb disease spread will look remarkably familiar to those taking many of the same actions in 2020: isolation, quarantine, personal hygiene, disinfectant usage, limitations on public gatherings, and masks were all employed in an attempt to slow the pandemic. Eventually, after four waves, the disease disappeared, vanishing almost entirely by the early to mid 1920s. But not before wreaking havoc everywhere from San Francisco to Annapolis.

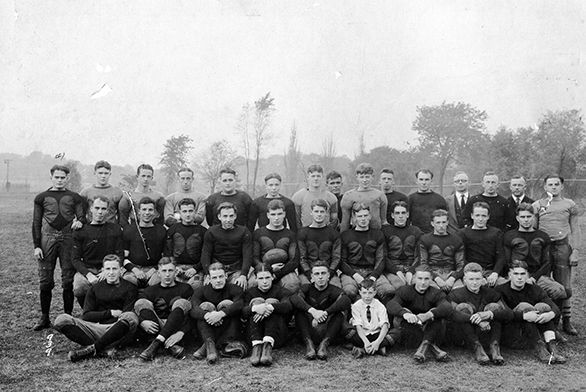

Back then, St. John’s looked—and functioned—much different than the unique liberal arts college of today. There was a St. John’s football team, the Black and Orange, which in 1899 defeated the University of Maryland 62-0, making the front page of the Washington Post. There were fewer buildings and more students, leading the college to house many Johnnies off campus. While it had a liberal arts foundation, the college of the early 20th century was known as a military school: 705 St. John’s students and alumni served as officers or enlisted soldiers in the armed forces during World War I.

By the time many of those students began travelling to campus in fall 1918, the existence of the flu in the United States had been officially acknowledged (though wartime self-censorship and misreporting led to the disease being termed the “Spanish Flu”). Nonetheless, students arrived at St. John’s on schedule in September to become members of the Students’ Army Training Corps. The rest is history: the flu spread and chaos ran rampant, with extraordinary circumstances forcing the college to take extraordinary action to keep its community safe.

And unfortunately, that’s about all we know. There aren’t many other pieces of recorded information regarding the flu and the 1918–19 academic year; it’s unclear whether there were further instances of quarantine or isolation, or other influenza outbreaks. It appears that the college was relatively unaffected by the pandemic. But reminders of the disease lingered. In several yearbooks in the years following 1918, there are multiple mentions of alumni who died or recovered from the disease, many of them military personnel.

So, what happened next for the college? What should we learn from the events of 1918? By the mid 1920s the military department at the college had functionally been dissolved; less than 20 years after the flu pandemic waned, St. John’s would change forever with the introduction of the New Program. And yet, walking through campus today—with masked Naval cadets in select residence halls and signs requiring masks and social distancing—it’s hard to shake the feeling that history lives and breathes in the quarantined college of 2020.

But perhaps those mostly empty brick buildings, many of them still standing from 1918, can also serve as a reminder. Even in the most unthinkable circumstances, Johnnies will persist in the pursuit of foundational ideas, truth, and virtue.