A Man for All Seasons

Spring 2017 | By Charlotte Jusinski for The College

Four framed lithographs of Frederick Douglass now shine on the first floor of Weigle Hall at St. John’s College in Santa Fe.

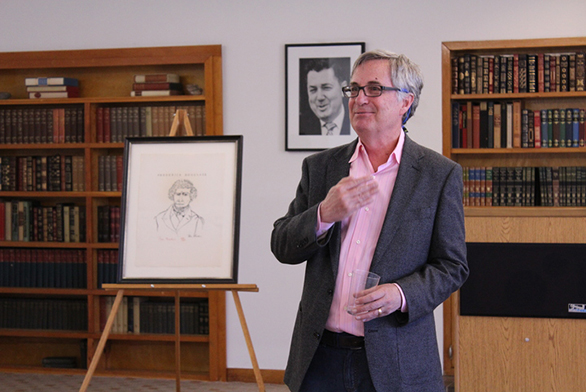

The lithographs, by famed American artist Ben Shahn, are a gift from President Mark Roosevelt, who greatly admires the former slave, abolitionist, author, and orator.

“I love Douglass and I love Shahn,” Roosevelt says. “And I believe that what you put on your walls is important.”

Roosevelt donated the pieces this spring at a ceremony attended by students, staff, and tutors. Douglass’s “The Constitution of the United States: Is it Pro-Slavery or Anti-Slavery?” is read in senior seminar.

Speaking at the ceremony, tutor Frank Pagano invited the audience to consider Shahn’s strikingly different depictions of Douglass.

“We see before us what a free man looks like. But to my eye we see four looks, almost four different men.”

After considering each image in great detail, Pagano asked: “Do the challenges to our freedom and our education require a man for all seasons, a man for all humanity, both the oppressed and the oppressor, the educated and the ignorant? We see before us the images of the liberally educated human being. We see courage, moderation, justice, and wisdom.”

Beyond his writings, Douglass is said to be the most photographed man of his time, and the book Picturing Frederick Douglass was presented to Roosevelt as a thanks for the gift. The book contains many of these images, including reproductions of three of the four Shahn lithographs.

Roosevelt recalled the story of Douglass trying to gain access to President Lincoln after the second inaugural speech on March 4, 1865. As Douglass stood in a crowd of white men, Lincoln called to him: “Here comes my friend Frederick Douglass.” This simple statement, within the complex context of the time, was a remarkable moment for the abolitionist movement and for America’s expanding definition of justice.

But, Roosevelt said, “I hesitate to make Douglass important to me or to anybody because of his relationship to Lincoln, because that minimizes him.” He pointed out that Douglass was frustrated with Lincoln’s slow progress toward allowing African Americans to fight in the war and toward emancipation.

“But eventually Douglass’s own incredible capacity for forgiveness made him continue to grow in closeness to and admiration for Lincoln, which I think says something about both of them.”